Who cares about climate change? And what should we call it?

I decided to answer these grand questions, using Google Trends, a tool which allows you to plot search frequency over time and compare different search terms and different countries. It’s a great little tool although it still lacks some important functionality and sometimes the results are a little… unexpected.

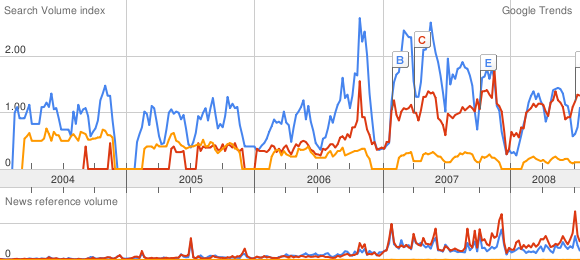

The first thing I wanted to know was what terms people are searching for on the topic of climate change. My impression was that the term greenhouse effect was used when the science first started floating around in the 70s and 80s, then global warming came to describe the overall problem, and more recently climate change took over as the dominant phrase. Google trends is the perfect tool to test this hypothesis (although unfortunately it doesn’t go back earlier than 2004). This graph shows the search volume of the three terms over time:

So, searches for greenhouse effect are small and declining, searches for global warming are large, erratic and increasing, and searches for climate change are somewhere in between. Not quite what I was expecting. The News volume graph (the second graph above) is a bit closer to what I expected – although the scale is too squashed to see very clearly, the two main terms appear to be fairly close together, but climate change has overtaken since the end of 2007.

There are some interesting variations over time. It’s impossible not to notice the sudden dips at the end of each year, and the longer dips mid-year. No-one cares about these serious topics when they’re on holidays. The big spike in climate change in 2006 corresponds to the release of the Stern Review on 30 Oct, which marks the beginning of the turning point in world interest. This was followed by the release of the IPCC’s alarming Fourth Assessment Report on 2 Feb 2007, generating another spike, and then the Bali climate change conference in Nov 2007, when negotiations for a successor to the Kyoto treaty began.

Google Trends can also show which countries are the most prolific searchers for these terms. For global warming for example, the top country is, of course, Indonesia.

Huh? Let’s take a closer look at that. Here are the top ten countries for GW and CC:

| Position |

Global Warming |

Climate Change |

| 1 |

Indonesia |

Australia |

| 2 |

Philippines |

New Zealand |

| 3 |

South Africa |

South Africa |

| 4 |

India |

United Kingdom |

| 5 |

Australia |

Canada |

| 6 |

New Zealand |

Ireland |

| 7 |

Singapore |

Singapore |

| 8 |

United States |

Philippines |

| 9 |

Malaysia |

India |

| 10 |

Canada |

United States |

It’s difficult to decode what’s happening here, but I’ll do my best. Indonesia, when plotted on its own, had basically no interest at all in global warming until mid-2006, presumably when preparations and press coverage for the Bali conference began. There is of course a huge spike in November of that year. Indonesia actually has a great deal to loose – and gain – from the current international negotiations. As a vast archipelago of islands it is more vulnerable than many other countries to rising sea levels; on the other hand, if they are able to claim carbon credits for their vast forests, it would bring substantial economic benefits to the country.

The swell of interest in the Philippines is even more of a mystery. Like Indonesia they have thousands of tiny islands which will be threatened by rising seas… perhaps fear is driving them into a desperate search for information?

As for climate change, my chest puffs out in pride to see Australia at the top of that list. It’s good to see we care about something. The US comes a paltry and unsurprising tenth. Tsk tsk – time for some grass roots action, guys.

Of course these comparisons are not entirely fair for linguistic reasons. Most non-english speaking countries have their own translation of global warming – apparently Indonesia and the Philippines just use the english words. Google Trends doesn’t allow any kind of multi-lingual comparison.

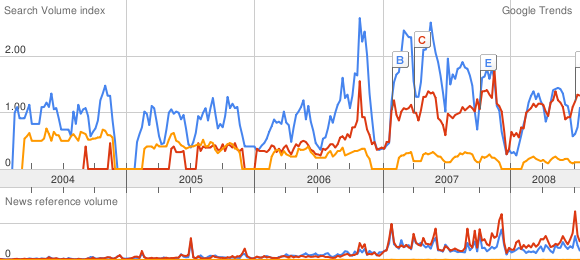

Speaking of linguistics, I’m tempted to return to the climate change / global warming distinction. Looking just at Australia (same colours as previously) we get the following graph:

This is pretty much as I expected. CC was virtually unknown before 2004, but has since grown to be just as, if not more important than GW. The UK gives a similar result, whereas the US lookes more like the first graph above. I’m not sure if there is much significance in this other than cultural preference.

Where did the term climate change come from? Here is the Wikipedia explanation:

The term “global warming” refers to the warming in recent decades and its projected continuation, and implies a human influence. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) uses the term “climate change” for human-caused change, and “climate variability” for other changes. The term “climate change” recognizes that rising temperatures are not the only effect.

I seem to recall a conspiracy theory a while back that suggested that the term climate change was invented by spin doctors from [insert evil organisation of your choice here] because it sounded more benign than global warming. That’s almost certainly nonsense (Update: Or not. See comments). CC is a more scientifically accurate term, and it more accurately describes the probable negative effects. If the only consequence was the warming of the earth, then the worst we would have to put with would be rising sea levels, diminishing sources of fresh water in some regions and disease epidemics. But focusing on these events, utterly catastrophic though they will be, is only part of the story. The climate will also change in ways that we are only now beginning to be able to predict – floods, droughts, cyclones and hurricanes will become more frequent, and once-reliable rainfall patterns will change, threatening our food production. Climate change, for me, is a more all-encompassing term.

Nevertheless, the (mostly Indonesian?) people have spoken, and they chose global warming. For some reason, that doesn’t satisfy me. I’m going to settle this with a straight, no frills Google search:

Climate change – 55,600,000

Global warming – 52,200,000

CC wins it by a nose!