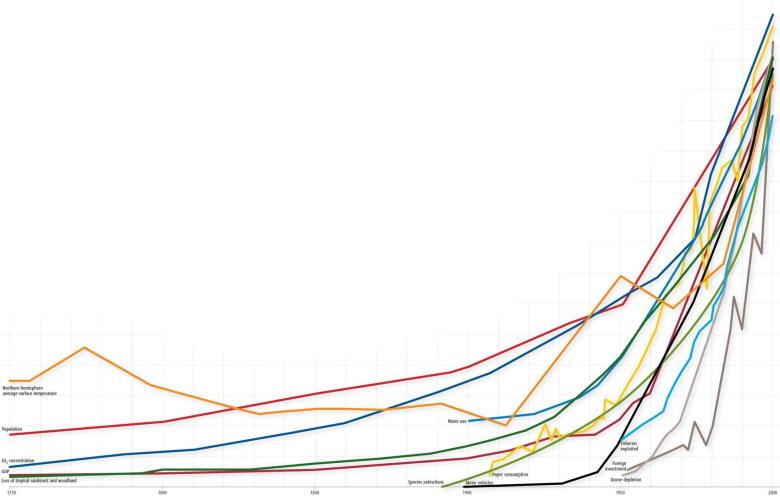

The government tonight released the budget for 2009-10. The big themes were infrastructure spending and debt, but I want to focus specifically on the programs relevant to climate change. Robert Merkel at LP rated it as having a “distinctly camouflage mottled hue”, but I’m a little more positive, albeit with some criticisms. See my analysis below.

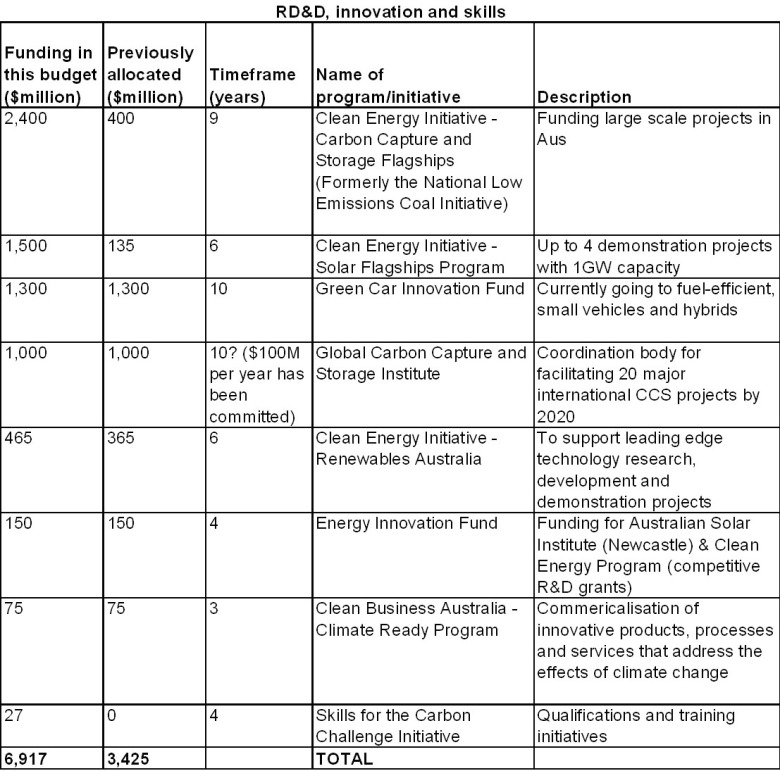

RD&D, innovation and skills

The biggest area of spending, and the biggest increase in spending, came in what I have categorised as RD&D, innovation and skills. Then headline items in this area are under the umbrella of the $4.3 billion Clean Energy Initiative, which includes $3 billion of new money – mostly going to Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and the Solar Flagships Program (which will fund up to 4 very large solar thermal or photovoltaic installations, totaling 1GW of capacity). There is also a $1.3 billion Green Car Innovation Fund, and $100 million per year for the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute, both 10 year programs that were announced last year.

So by my calculations (see below), this adds up to $6.9 billion of commitments in this area, up from $3.4 billion previously. One important point is that in the area of low carbon stationary energy, $4.9 billion is allocated to specific technologies – CCS and large scale solar, compared with only $615 million to technology neutral, competitive funding. Admittedly, there are several competing technology options within CCS and solar, but this amounts to a fairly significant picking of winners by the government. I’ll come back to this difficult issue in a future post.

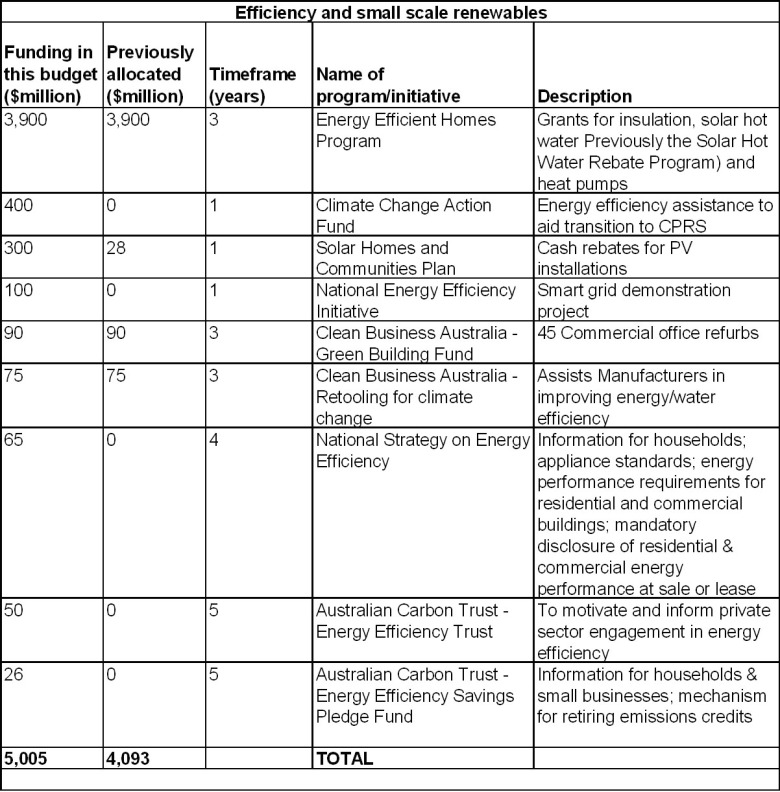

Energy efficiency and small scale renewables

On the demand side of the energy equation, we have energy efficiency and small scale renewables. By my calculations, this budget is committing about $5 billion to this category, up from $4.1 billion before the CPRS was announced. Most of this is going towards domestic insulation and solar hot water through the Energy Efficient Homes Program. There seems to be a confusing array of 9 overlapping programs in this area, with various timeframes, 5 of which are relevant to domestic and 7 of which are relevant to business. Why so many? The $100 million smart grid funding is welcome, but should be larger and allocated to a wider national roll-out, rather than another demonstration project. The technology is well established and has been demonstrated ad-nauseum.

Miscellaneous spending includes $98 million allocated to Australia Climate Change Regulatory Authority (which will oversee the CPRS) and the National Carbon Accounting Toolbox.

Conclusions

Overall, there are some important boosts to the green economy in this budget. But is it enough, and is it well directed? I would have liked to see more going towards Renewables Australia and the Energy Innovation Fund, which are both good, technology neutral funds. Also, the Clean Business Australia program could have been a lot bigger, particularly in comparison to the massive Energy Efficient Homes package. Business energy efficiency is less visible to voters, but equally important. As I’ve already mentioned, more on Smart Grids would also have been welcome.

But I do support the big spending committments that were made, in CCS, large-scale solar, and green cars. Overall, I give the 2009/10 Budget 6 1/2 green stars out of 10.